2024 (Aug.): NY Regents - US History & Government

By Sara Cowley

star

star

star

star

star

Last updated 27 days ago

37 questions

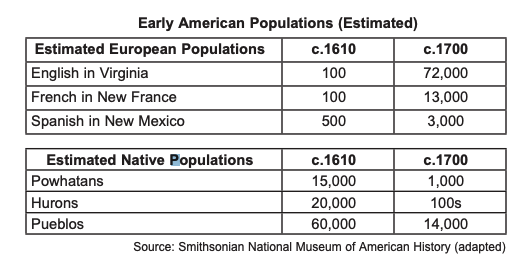

Which statement is best supported by the information in this chart?

Which statement is best supported by the information in this chart?

What was a main cause of the population trend shown in this chart?

What was a main cause of the population trend shown in this chart?

JUST ARRIVED, The Justitia, Captain Kidd, With About ONE HUNDRED AND THIRTY healthy SERVANTS,

CONSISTING of Men, Women, and Boys; among whom are TRADESMEN, such as Carpenters and Joiners, Bricklayers and Plaisterers [plasterers], Shoemakers, Barbers and Hair Dressers, several Weavers, Cutlers, Curriers, and Bakers, a Tanner, a Tailor and Staymaker, a Blacksmith, a Painter, a Printer, a Bookbinder, a Miller, a Stocking Weaver, a Schoolmaster, a Hatter, a Silk Dryer, and others. There are also many Farmers, and other Country Labourers, Gentlemen’s Servants, etc. etc. The Sale will commence at Leeds Town, on Wednesday the 22d Instant (March) and be continued till all are sold. A reasonable Credit will be allowed, the Purchasers giving Bond, with approved Security, to THOMAS HODGE.

Source: Virginia Gazette, March 18, 1775 (adapted)

Notices such as this, published in the Virginia Gazette in 1775, demonstrate that

Notices such as this, published in the Virginia Gazette in 1775, demonstrate that

Based on this notice, what was the main reason immigrants were willing to enter into years of indentured servitude in British North America?

Based on this notice, what was the main reason immigrants were willing to enter into years of indentured servitude in British North America?

... At a very large and respectable meeting of the freeholders and freemen of the city and county of Philadelphia, on June 18, 1774. Thomas Willing, John Dickinson, chairmen.

- Resolved, That the act of parliament, for shutting up the port of Boston, is unconstitutional, oppressive to the inhabitants of that town, dangerous to the liberties of the British colonies, and that therefore, considering our brethren, at Boston, as suffering in the common cause of America.

- That a congress of deputies from the several colonies, in North America, is the most probable and proper mode of procuring [obtaining] relief for our suffering brethren, obtaining redress of American grievances, securing our rights and liberties, and re-establishing peace and harmony between Great Britain and these colonies, on a constitutional foundation.

- That a large and respectable committee be immediately appointed for the city and county of Philadelphia, to correspond with the sister colonies and with the several counties in this province, in order that all may unite in promoting and endeavoring to attain the great and valuable ends, mentioned in the foregoing resolution. . . .

Source: Pennsylvania Resolutions on the Boston Port Act, June 20, 1774

The June 1774 meeting of Philadelphia freemen was called as a direct result of

The June 1774 meeting of Philadelphia freemen was called as a direct result of

How did the Pennsylvania Resolutions move the colonies toward independence?

How did the Pennsylvania Resolutions move the colonies toward independence?

Base your answers to questions 7 and 8 on the passage below and on your knowledge of social studies.

... But to the question—without force what can restrain the Congress from making such laws as they please? What limits are there to their authority? I fear none at all. For surely it cannot be justly said that they have no power but what is expressly given to them, when by the very terms of their creation they are vested with the powers of making laws in all cases—necessary and proper; when from the nature of their power, they must necessarily be the judges what laws are necessary and proper...

Source: Antifederalist No. 46, November 2, 1788

Based on this passage, why did Antifederalists oppose ratification of the Constitution?

Based on this passage, why did Antifederalists oppose ratification of the Constitution?

Which action was taken to deal with the criticism expressed in this passage?

Which action was taken to deal with the criticism expressed in this passage?

Base your answers to questions 9 and 10 on the excerpt below and on your knowledge of social studies.

. . . It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is. Those who apply the rule to particular cases, must of necessity expound [explain] and interpret that rule. If two laws conflict with each other, the courts must decide on the operation of each.

So if a law be in opposition to the constitution; if both the law and the constitution apply to a particular case, so that the court must either decide that case conformably [according] to the law, disregarding the constitution; or conformably to the constitution, disregarding the law; the court must determine which of these conflicting rules governs the case; This is of the very essence of judicial duty.

If, then, the courts are to regard the constitution, and the constitution is superior to any ordinary act of the legislature, the constitution, and not such ordinary act, must govern the case to which they both apply. . . .

Source: Chief Justice John Marshall, majority opinion, Marbury v. Madison, February 24, 1803

In this excerpt from Marbury v. Madison, Chief Justice Marshall established the precedent that the Supreme Court

In this excerpt from Marbury v. Madison, Chief Justice Marshall established the precedent that the Supreme Court

What is one important consequence of the Supreme Court’s decision in Marbury v. Madison?

What is one important consequence of the Supreme Court’s decision in Marbury v. Madison?

Base your answers to questions 11 and 12 on the passage below and on your knowledge of social studies.

. . . I never saw my mother, to know her as such, more than four or five times in my life; and each of these times was very short in duration, and at night. She was hired by a Mr. Stewart, who lived about twelve miles from my home. She made her journeys to see me in the night, traveling the whole distance on foot, after the performance of the day’s work. She was a field hand, and a whipping is the penalty of not being in the field at sunrise, unless a slave has special permission from his or her master to the contrary—a permission which they seldom get, and one that gives to him that proud name of being a kind master. I do not recollect of ever seeing my mother by the light of day. She was with me in the night. She would lie down with me and get me to sleep, but long before I waked she was gone. Very little communication ever took place between us. Death soon ended what little we could have while she lived, and with it her hardships and suffering. She died when I was about seven years old, on one of my master’s farms, near Lee’s Mills. I was not allowed to be present during her illness, at her death, or burial. She was gone long before I knew any thing about it. Never having enjoyed, to any considerable extent, her soothing presence, her tender and watchful care, I received the tidings of her death with much the same emotions I should have probably felt at the death of a stranger. . . .

Source: Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, 1845

What was one primary characteristic of slavery in the United States?

What was one primary characteristic of slavery in the United States?

Which three individuals would historians most likely study in conjunction with this passage?

Which three individuals would historians most likely study in conjunction with this passage?

Base your answers to questions 13 and 14 on the excerpt below and on your knowledge of social studies.

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled,

Section 1. Every contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy in restraint of trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations, is hereby declared to be illegal. Every person who shall make any such contract or engage in any such combination or conspiracy, shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor and, on conviction thereof, shall be punished by fine not exceeding five thousand dollars, or by imprisonment not exceeding one year, or by both said punishments, at the discretion of the court. . . .

Source: The Sherman Antitrust Act, December 2, 1890

Congress enacted the Sherman Antitrust Act so that

Congress enacted the Sherman Antitrust Act so that

The greatest weakness of the Sherman Antitrust Act was that it

The greatest weakness of the Sherman Antitrust Act was that it

Based on this graph, the largest number of immigrants came to the United States during periods of

Based on this graph, the largest number of immigrants came to the United States during periods of

The main reason for declining immigration in the 1920s was that the United States

The main reason for declining immigration in the 1920s was that the United States

Base your answers to questions 17 and 18 on the cartoon below and on your knowledge of social studies.

"Touch Not a Single Bough [Branch]"

Source: Literary Digest, August 9, 1919 (adapted)

Which constitutional principle is the focus of this cartoon?

Which constitutional principle is the focus of this cartoon?

What was one reason for the Senate's action illustrated in this cartoon?

What was one reason for the Senate's action illustrated in this cartoon?

Base your answers to questions 19 and 20 on the passage below and on your knowledge of social studies.

. . . She reminded FDR [Franklin D. Roosevelt] of her role in the Civilian Conservation Corps, the Public Works Program, and the labor aspects of the National Industrial Recovery Act. She reminded him that he had entrusted her with the research, legislative program, popularization, and establishment of unemployment insurance, old-age pensions, and the welfare program. She described how she had reduced child labor in America, minimized workplace accidents, and converted the Bureau of Labor Statistics into a “trusted” source of information. The Fair Labor Standards Act brought about the minimum wage, the concept of the forty-hour workweek, and paying for overtime. She greatly expanded the U.S. Conciliation Service in dealing with strikes. She dealt with many labor questions during the war, when skilled manpower was vital and women moved into formerly male jobs. . . .

Source: Kirstin Downey, The Woman Behind the New Deal: The Life of Frances Perkins, FDR's Secretary of Labor and His Moral Conscience, Doubleday, 2009

As Secretary of Labor, what was Frances Perkins’ primary role in the Roosevelt administration?

As Secretary of Labor, what was Frances Perkins’ primary role in the Roosevelt administration?

What were two of the New Deal’s permanent legacies that Frances Perkins helped to create?

What were two of the New Deal’s permanent legacies that Frances Perkins helped to create?

Base your answers to questions 21 and 22 on the passage below and on your knowledge of social studies.

. . . It is logical that the United States should do whatever it is able to do to assist in the return of normal economic health in the world, without which there can be no political stability and no assured peace. Our policy is directed not against any country or doctrine but against hunger, poverty, desperation and chaos. Its purpose should be the revival of a working economy in the world so as to permit the emergence of political and social conditions in which free institutions can exist. Such assistance, I am convinced, must not be on a piece-meal basis as various crises develop. Any assistance that this Government may render in the future should provide a cure rather than a mere palliative [relief]. Any government that is willing to assist in the task of recovery will find full cooperation, I am sure, on the part of the United States Government. Any government which maneuvers to block the recovery of other countries cannot expect help from us. Furthermore, governments, political parties or groups which seek to perpetuate human misery in order to profit therefrom politically or otherwise will encounter the opposition of the United States. . . .

Source: Secretary of State George C. Marshall, Harvard University, June 1947

Which foreign policy supported the goals expressed in this passage?

Which foreign policy supported the goals expressed in this passage?

Secretary of State George C. Marshall’s plan was partly a response to the

Secretary of State George C. Marshall’s plan was partly a response to the

Base your answers to questions 23 and 24 on the passage below and on your knowledge of social studies.

...Those of us who shout the loudest about Americanism in making character assassinations are all too frequently those who, by our own words and acts, ignore some of the basic principles of Americanism:The right to criticize. The right to hold unpopular beliefs. The right to protest. The right of independent thought. The exercise of these rights should not cost one single American citizen his reputation or his right to a livelihood nor should he be in danger of losing his reputation or livelihood merely because he happens to know someone who holds unpopular beliefs. Who of us does not? Otherwise none of us could call our souls our own. Otherwise thought control would have set in. The American people are sick and tired of being afraid to speak their minds lest they be politically smeared as “Communists” or “Fascists” by their opponents. Freedom of speech is not what it used to be in America. It has been so abused by some that it is not exercised by others. ...

Source: Senator Margaret Chase Smith, Declaration of Conscience Speech, June 1, 1950

In this passage, Senator Smith argues that those who question an individual's loyalty to the United States should be reminded that

In this passage, Senator Smith argues that those who question an individual's loyalty to the United States should be reminded that

This 1950 “Declaration of Conscience” speech by Senator Smith was written in response to

This 1950 “Declaration of Conscience” speech by Senator Smith was written in response to

Base your answers to questions 25 and 26 on the excerpt below and on your knowledge of social studies.

... Today, education is perhaps the most important function of state and local governments.Compulsory school attendance laws and the great expenditures for education both demonstrate our recognition of the importance of education to our democratic society. It is required in the performance of our most basic public responsibilities, even services in the armed forces. It is the very foundation of good citizenship. Today it is a principal instrument in awakening the child to cultural values, in preparing him for later professional training, and in helping him to adjust normally to his environment. In these days, it is doubtful that any child may reasonably be expected to succeed in life if he is denied the opportunity of an education. Such an opportunity, where the state has undertaken to provide, is a right which must be made available to all on equal terms.We come then to the question presented: does segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race, even though the physical facilities and other “tangible” factors may be equal, deprive the children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities? We believe that it does. ...

Source: Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, May 17, 1954

As a result of this Supreme Court decision, the Court ordered that

As a result of this Supreme Court decision, the Court ordered that

Which government action further promoted equality in the United States?

Which government action further promoted equality in the United States?

The Patriot Act was a direct response to

The Patriot Act was a direct response to

What is one impact of the Patriot Act on the United States

What is one impact of the Patriot Act on the United States

DOCUMENT 1

DEAR EDITOR: Like all true Americans, my greatest desire at this time, this crucial point of our history, is a desire for a complete victory over the forces of evil, which threaten our existence today. Behind that desire is also a desire to serve, this, my country, in the most advantageous way. Most of our leaders are suggesting that we sacrifice every other ambition to the paramount one, victory. With this I agree; but I also wonder if another victory could not be achieved at the same time. . . . Being an American of dark complexion and some 26 years, these questions flash through my mind: “Should I sacrifice my life to live half American?” “Will things be better for the next generation in the peace to follow?” “Would it be demanding too much to demand full citizenship rights in exchange for the sacrificing of my life?” “Is the kind of America I know worth defending?” “Will America be a true and pure democracy after this war?” “Will colored Americans suffer still the indignities that have been heaped upon them in the past?”. . . . I suggest that while we keep defense and victory in the forefront that we don’t lose sight of our fight for true democracy at home. The “V for Victory” sign is being displayed prominently in all so-called democratic countries which are fighting for victory over aggression, slavery and tyranny. If this V sign means that to those now engaged in this great conflict then let colored Americans adopt the double VV for a double victory: The first V for victory over our enemies from without, the second V for victory over our enemies within. For surely those who perpetrate these ugly prejudices here are seeking to destroy our democratic form of government just as surely as the Axis forces. . . . In conclusion let me say that though these questions often permeate my mind, I love America and am willing to die for the America I know will someday become a reality. JAMES G. THOMPSON. Source: James G. Thompson, letter to the editor, Pittsburgh Courier, originally printed January 31, 1942; reprinted April 11, 1942 (adapted)

Task: Based on your reading and analysis of these documents, apply your social studies knowledge and skills to write a short essay of two or three paragraphs in which you:- Describe the historical context surrounding these documents

- Identify and explain the relationship between the events and/or ideas found in these documents (Cause and Effect, or Similarity/Difference, or Turning Point)

Guidelines:- In your short essay, be sure to

- Develop all aspects of the task

- Incorporate relevant outside information

- Support the task with relevant facts and examples

You are not required to include a separate introduction or conclusion in your short essay of two or three paragraphs.

Task: Based on your reading and analysis of these documents, apply your social studies knowledge and skills to write a short essay of two or three paragraphs in which you:

- Describe the historical context surrounding these documents

- Identify and explain the relationship between the events and/or ideas found in these documents (Cause and Effect, or Similarity/Difference, or Turning Point)

Guidelines:

- In your short essay, be sure to

- Develop all aspects of the task

- Incorporate relevant outside information

- Support the task with relevant facts and examples

You are not required to include a separate introduction or conclusion in your short essay of two or three paragraphs.

DOCUMENT 1

The following excerpt was written by Hinton Rowan Helper, the son of a North Carolina farmer.

. . . In our opinion, an opinion which has been formed from data obtained by assiduous [careful] researches, and comparisons, from laborious investigation, logical reasoning, and earnest reflection, the causes which have impeded [slowed] the progress and prosperity of the South, which have dwindled our commerce, and other similar pursuits, into the most contemptible insignificance; sunk a large majority of our people in galling [distressing] poverty and ignorance, rendered a small minority conceited and tyrannical, and driven the rest away from their homes; entailed [imposed] upon us a humiliating dependence on the Free States; disgraced us in the recesses of our own souls, and brought us under reproach in the eyes of all civilized and enlightened nations—may all be traced to one common source, and there find solution in the hateful and horrible word, that was ever incorporated into the vocabulary of human economy—Slavery! . . .

Source: Hinton Helper, The Impending Crisis of the South: How To Meet It, 1857

Task: Based on your reading and analysis of these documents, apply your social studies knowledge and skills to write a short essay of two or three paragraphs in which you:- Describe the historical context surrounding documents 1 and 2

- Analyze Document 1 and explain how audience, or purpose, or bias, or point of view affects this document’s use as a reliable source of evidence

Guidelines:

In your short essay, be sure to- Develop all aspects of the task

- Incorporate relevant outside information

- Support the task with relevant facts and examples

You are not required to include a separate introduction or conclusion in your short essay of two or three paragraphs.

Task: Based on your reading and analysis of these documents, apply your social studies knowledge and skills to write a short essay of two or three paragraphs in which you:

- Describe the historical context surrounding documents 1 and 2

- Analyze Document 1 and explain how audience, or purpose, or bias, or point of view affects this document’s use as a reliable source of evidence

Guidelines:

In your short essay, be sure to

- Develop all aspects of the task

- Incorporate relevant outside information

- Support the task with relevant facts and examples

You are not required to include a separate introduction or conclusion in your short essay of two or three paragraphs.

Document 1a

Before the declaration of war in 1917, the idea of sending U.S. troops to fight the Germans and save the British was not popular with the American people. However, once Congress declared war, there was considerable pressure to stifle [quiet] dissent about the war. Elihu Root, one of President Wilson’s advisers, said in early 1917, “We must have no criticism now.” Police surveillance increased, and Americans were encouraged to report their neighbors’ “disloyal” acts. Congress enacted the Espionage Act of 1917, which made acts of insubordination and disloyalty punishable by prison terms of up to twenty years. It was the first time since the Alien and Sedition Acts (1798) early in the nation’s history that criticism of government had been criminalized. Sponsors said that tolerating disloyal public statements might undermine efforts to draft and recruit young people into military service. More than 2,000 people were prosecuted under the act. One of them was Charles Schenck, general secretary of Philadelphia’s Socialist Party. In 1917 the party directed Schenck to prepare a leaflet that would be distributed to young men conscripted in the recently enacted military draft. Source: Tony Mauro, Illustrated Great Decisions of the Supreme Court, CQ Press, 2006

Document 1b

Opposition to America’s wars was not new. Antiwar movements had emerged during the War of 1812, the war against Mexico (1846–48), and the 1898 war against Spain. But World War I saw the development of a much more consequential opposition, numbering in the millions, drawing on many sectors of society, and powerful enough to inspire a massive government crackdown that included thousands of arrests, the suppression of newspapers and organizations, and a tightly coordinated public information campaign that branded dissenters as enemy agents and dangerous subversives. World War I proved pivotal for German Americans, many of whom mobilized to promote American neutrality during the years 1914–1916 only to become targets of suspicion and hatred when the US entered the war in 1917. It was pivotal too for the Socialist Party, the Industrial Workers of the World, and other radical organizations that opposed American involvement. After 1917, radicals supplied much of the energy for the antiwar movement, and radical organizations paid dearly for their dissent. The government campaign to suppress antiwar opposition turned into a generalized red scare that continued into the 1920s. The American left was never the same. Source: Pacific Northwest Labor and Civil Rights Projects, University of Washington, 2009

Based on these documents, what is one historical circumstance that led to the restriction of individual rights during World War I?

Based on these documents, what is one historical circumstance that led to the restriction of individual rights during World War I?

Document 2a

Congress passed, and Wilson signed, in June of 1917, the Espionage Act. From its title one would suppose it was an act against spying. However, it had a clause that provided penalties up to twenty years in prison for “Whoever, when the United States is at war, shall willfully cause or attempt to cause insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny, or refusal of duty in the military or naval forces of the United States, or shall willfully obstruct the recruiting or enlistment service of the U.S. …” Unless one had a theory about the nature of governments, it was not clear how the Espionage Act would be used. It even had a clause that said “nothing in this section shall be construed to limit or restrict … any discussion, comment, or criticism of the acts or policies of the Government.” … But its double-talk concealed a singleness of purpose. The Espionage Act was used to imprison Americans who spoke or wrote against the war. Source: Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States, 1492–Present, Harper Perennial, 2001

Document 2b

Based on these documents, what was one effort to address the issue of individual rights during World War I?

Based on these documents, what was one effort to address the issue of individual rights during World War I?

Document 3

. . .More than all, the citizen and his representative in Congress in time of war must maintain his right of free speech. More than in times of peace it is necessary that the channels for free public discussion of governmental policies shall be open and unclogged. I believe, Mr. President, that I am now touching upon the most important question in this country today—and that is the right of the citizens of this country and their representatives in Congress to discuss in an orderly way frankly and publicly and without fear, from the platform and through the press, every important phase of this war; its causes, the manner in which it should be conducted, and the terms upon which peace should be made. The belief which is becoming widespread in this land that this most fundamental right is being denied to the citizens of this country is a fact the tremendous significance of which, those in authority have not yet begun to appreciate. I am contending, Mr. President, for the great fundamental right of the sovereign people of this country to make their voice heard and have that voice heeded upon the great questions arising out of this war, including not only how the war shall be prosecuted [conducted] but the conditions upon which it may be terminated with a due regard for the rights and the honor of this nation and the interests of humanity. . . . Source: Senator Robert M. La Follette Sr., “Free Speech in Wartime,” October 6, 1917, Congressional Record, 65th Congress

According to Senator Robert La Follette, what is one reason freedom of speech is important during wartime?

According to Senator Robert La Follette, what is one reason freedom of speech is important during wartime?

Document 4

The first legal challenge to the new law came early in January 1919, when three separate Espionage Act cases were argued before the U.S. Supreme Court. The Court had never before reviewed a free speech challenge to a federal statute. One of the cases, Schenck v. United States, began two years earlier when Charles Schenck, a prominent socialist, was arrested and tried for printing and distributing a leaflet that urged his fellow Americans to resist the draft. “A conscript [draftee] is little better than a convict,” it read. “He is deprived of his liberty and of his right to think and act as a free man.” In all three Espionage Act cases, the justices voted unanimously to uphold the convictions. But it was in the Schenck opinion that associate justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. created a new legal standard that served as the basis for all three decisions. Holmes, one of the Court’s more liberal members, conceded that the language used by the defendants would be acceptable in times of peace. But he stressed that “the character of every act depends upon the circumstances in which it is done. The most stringent [strict] protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic. The question in every case,” Holmes concluded, “is whether the words used are used in such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive [real] evils that Congress has a right to prevent.” Source: Haynes, Chaltain, and Glisson, A Documentary History Of First Amendment Rights in America, Oxford University Press, 2006

Based on this document, how did the decision in Schenck v. United States impact individual rights during wartime? [1]

Based on this document, how did the decision in Schenck v. United States impact individual rights during wartime? [1]

Document 5

Eugene Debs was arrested for giving an antiwar speech and later convicted of violating the Espionage Act. His conviction was upheld by the Supreme Court in 1919. In 1921, President Warren G. Harding made the decision to release Debs from prison. Unquestionably, however, President Harding’s pardon of Eugene Debs and other political prisoners was one of his most important and underappreciated legacies. Specifically, his act was a singular contribution to the development of the pardon practice under Article II, Section 2, of the Constitution. These commutations [pardons] served as a check on potential abuse by both coequal branches of government. Harding’s strategic use of the presidential pardon helped undo the damage done by a war-frenzied Congress in enacting the Espionage and Sedition Acts, which had been compounded by the failure of the Supreme Court to defend the First Amendment of the Constitution. It was an impressive demonstration of constitutional authority by a president. Seen in this context, Harding’s call for a “return to normalcy” hardly seems as trite [insignificant] as it is often portrayed in historical texts. His ending the abuses of the Sedition Act and the American Protective League did more than simply effect a nonviolent transition back to prewar conditions. The action also clearly showed that President Warren Harding understood the critical need for the executive to use constitutional power to counterbalance pernicious [harmful] legislation or unwise court rulings that might threaten core freedoms under the U.S. Constitution. Source: Ken Gormley, The Presidents and the Constitution, A Living History, New York University Press, 2016 (adapted)

According to Ken Gormley, how did President Harding’s pardon of Eugene Debs impact individual rights after World War I? [1]

According to Ken Gormley, how did President Harding’s pardon of Eugene Debs impact individual rights after World War I? [1]

Document 6

. . .During World War II, President Roosevelt ordered the internment of more than 110,000 individuals of Japanese descent, two-thirds of whom were American citizens. Men, women, and children were locked away in detention camps for the better part of three years, for no reason other than their race. Faced with the threat of Soviet espionage, sabotage, and subversion during the Cold War, the government instituted loyalty programs, legislative investigations, blacklists, and criminal prosecutions to ferret out [find] and punish those suspected of “disloyalty.” It was an era scarred by the actions of Senator Joseph McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee. During the Vietnam War, the Johnson and Nixon administrations initiated surreptitious [secret] programs of surveillance and infiltration in order to disrupt and neutralize those who opposed the war, prosecuted dissenters for burning their draft cards and expressing contempt for the American flag, and attempted to prevent the New York Times and the Washington Post from publishing the Pentagon Papers. . . . Source: Geoffrey R. Stone, War and Liberty, An American Dilemma: 1790 to the present, W. W. Norton & Company, 2007

According to Geoffrey Stone, what is one way individual rights during wartime continued to be an issue after World War I?

According to Geoffrey Stone, what is one way individual rights during wartime continued to be an issue after World War I?

Document 1a

Before the declaration of war in 1917, the idea of sending U.S. troops to fight the Germans and save the British was not popular with the American people. However, once Congress declared war, there was considerable pressure to stifle [quiet] dissent about the war. Elihu Root, one of President Wilson’s advisers, said in early 1917, “We must have no criticism now.” Police surveillance increased, and Americans were encouraged to report their neighbors’ “disloyal” acts. Congress enacted the Espionage Act of 1917, which made acts of insubordination and disloyalty punishable by prison terms of up to twenty years. It was the first time since the Alien and Sedition Acts (1798) early in the nation’s history that criticism of government had been criminalized. Sponsors said that tolerating disloyal public statements might undermine efforts to draft and recruit young people into military service. More than 2,000 people were prosecuted under the act. One of them was Charles Schenck, general secretary of Philadelphia’s Socialist Party. In 1917 the party directed Schenck to prepare a leaflet that would be distributed to young men conscripted in the recently enacted military draft. Source: Tony Mauro, Illustrated Great Decisions of the Supreme Court, CQ Press, 2006

Document 1b

Opposition to America’s wars was not new. Antiwar movements had emerged during the War of 1812, the war against Mexico (1846–48), and the 1898 war against Spain. But World War I saw the development of a much more consequential opposition, numbering in the millions, drawing on many sectors of society, and powerful enough to inspire a massive government crackdown that included thousands of arrests, the suppression of newspapers and organizations, and a tightly coordinated public information campaign that branded dissenters as enemy agents and dangerous subversives. World War I proved pivotal for German Americans, many of whom mobilized to promote American neutrality during the years 1914–1916 only to become targets of suspicion and hatred when the US entered the war in 1917. It was pivotal too for the Socialist Party, the Industrial Workers of the World, and other radical organizations that opposed American involvement. After 1917, radicals supplied much of the energy for the antiwar movement, and radical organizations paid dearly for their dissent. The government campaign to suppress antiwar opposition turned into a generalized red scare that continued into the 1920s. The American left was never the same. Source: Pacific Northwest Labor and Civil Rights Projects, University of Washington, 2009

Document 2a

Congress passed, and Wilson signed, in June of 1917, the Espionage Act. From its title one would suppose it was an act against spying. However, it had a clause that provided penalties up to twenty years in prison for “Whoever, when the United States is at war, shall willfully cause or attempt to cause insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny, or refusal of duty in the military or naval forces of the United States, or shall willfully obstruct the recruiting or enlistment service of the U.S. …” Unless one had a theory about the nature of governments, it was not clear how the Espionage Act would be used. It even had a clause that said “nothing in this section shall be construed to limit or restrict … any discussion, comment, or criticism of the acts or policies of the Government.” … But its double-talk concealed a singleness of purpose. The Espionage Act was used to imprison Americans who spoke or wrote against the war. Source: Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States, 1492–Present, Harper Perennial, 2001

Document 2b

Document 3

. . .More than all, the citizen and his representative in Congress in time of war must maintain his right of free speech. More than in times of peace it is necessary that the channels for free public discussion of governmental policies shall be open and unclogged. I believe, Mr. President, that I am now touching upon the most important question in this country today—and that is the right of the citizens of this country and their representatives in Congress to discuss in an orderly way frankly and publicly and without fear, from the platform and through the press, every important phase of this war; its causes, the manner in which it should be conducted, and the terms upon which peace should be made. The belief which is becoming widespread in this land that this most fundamental right is being denied to the citizens of this country is a fact the tremendous significance of which, those in authority have not yet begun to appreciate. I am contending, Mr. President, for the great fundamental right of the sovereign people of this country to make their voice heard and have that voice heeded upon the great questions arising out of this war, including not only how the war shall be prosecuted [conducted] but the conditions upon which it may be terminated with a due regard for the rights and the honor of this nation and the interests of humanity. . . . Source: Senator Robert M. La Follette Sr., “Free Speech in Wartime,” October 6, 1917, Congressional Record, 65th Congress

Document 4

The first legal challenge to the new law came early in January 1919, when three separate Espionage Act cases were argued before the U.S. Supreme Court. The Court had never before reviewed a free speech challenge to a federal statute. One of the cases, Schenck v. United States, began two years earlier when Charles Schenck, a prominent socialist, was arrested and tried for printing and distributing a leaflet that urged his fellow Americans to resist the draft. “A conscript [draftee] is little better than a convict,” it read. “He is deprived of his liberty and of his right to think and act as a free man.” In all three Espionage Act cases, the justices voted unanimously to uphold the convictions. But it was in the Schenck opinion that associate justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. created a new legal standard that served as the basis for all three decisions. Holmes, one of the Court’s more liberal members, conceded that the language used by the defendants would be acceptable in times of peace. But he stressed that “the character of every act depends upon the circumstances in which it is done. The most stringent [strict] protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic. The question in every case,” Holmes concluded, “is whether the words used are used in such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive [real] evils that Congress has a right to prevent.” Source: Haynes, Chaltain, and Glisson, A Documentary History Of First Amendment Rights in America, Oxford University Press, 2006

Document 5

Eugene Debs was arrested for giving an antiwar speech and later convicted of violating the Espionage Act. His conviction was upheld by the Supreme Court in 1919. In 1921, President Warren G. Harding made the decision to release Debs from prison. Unquestionably, however, President Harding’s pardon of Eugene Debs and other political prisoners was one of his most important and underappreciated legacies. Specifically, his act was a singular contribution to the development of the pardon practice under Article II, Section 2, of the Constitution. These commutations [pardons] served as a check on potential abuse by both coequal branches of government. Harding’s strategic use of the presidential pardon helped undo the damage done by a war-frenzied Congress in enacting the Espionage and Sedition Acts, which had been compounded by the failure of the Supreme Court to defend the First Amendment of the Constitution. It was an impressive demonstration of constitutional authority by a president. Seen in this context, Harding’s call for a “return to normalcy” hardly seems as trite [insignificant] as it is often portrayed in historical texts. His ending the abuses of the Sedition Act and the American Protective League did more than simply effect a nonviolent transition back to prewar conditions. The action also clearly showed that President Warren Harding understood the critical need for the executive to use constitutional power to counterbalance pernicious [harmful] legislation or unwise court rulings that might threaten core freedoms under the U.S. Constitution. Source: Ken Gormley, The Presidents and the Constitution, A Living History, New York University Press, 2016 (adapted)

Document 6

. . .During World War II, President Roosevelt ordered the internment of more than 110,000 individuals of Japanese descent, two-thirds of whom were American citizens. Men, women, and children were locked away in detention camps for the better part of three years, for no reason other than their race. Faced with the threat of Soviet espionage, sabotage, and subversion during the Cold War, the government instituted loyalty programs, legislative investigations, blacklists, and criminal prosecutions to ferret out [find] and punish those suspected of “disloyalty.” It was an era scarred by the actions of Senator Joseph McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee. During the Vietnam War, the Johnson and Nixon administrations initiated surreptitious [secret] programs of surveillance and infiltration in order to disrupt and neutralize those who opposed the war, prosecuted dissenters for burning their draft cards and expressing contempt for the American flag, and attempted to prevent the New York Times and the Washington Post from publishing the Pentagon Papers. . . . Source: Geoffrey R. Stone, War and Liberty, An American Dilemma: 1790 to the present, W. W. Norton & Company, 2007

Task:

Using information from the documents and your knowledge of United States history, write an essay in which you:- Describe the historical circumstances surrounding this constitutional or civic issue

- Explain efforts by individuals, groups, and/or governments to address this constitutional or civic issue

- Discuss the extent to which the efforts were successful

Guidelines: In your essay, be sure to- Develop all aspects of the task

- Explain at least two efforts to address the issue

- Incorporate information from at least four documents

- Incorporate relevant outside information

- Support the theme with relevant facts, examples, and details

- Use a logical and clear plan of organization, including an introduction and a conclusion that are beyond a restatement of the theme

Task:

Using information from the documents and your knowledge of United States history, write an essay in which you:

- Describe the historical circumstances surrounding this constitutional or civic issue

- Explain efforts by individuals, groups, and/or governments to address this constitutional or civic issue

- Discuss the extent to which the efforts were successful

Guidelines: In your essay, be sure to

- Develop all aspects of the task

- Explain at least two efforts to address the issue

- Incorporate information from at least four documents

- Incorporate relevant outside information

- Support the theme with relevant facts, examples, and details

- Use a logical and clear plan of organization, including an introduction and a conclusion that are beyond a restatement of the theme